When I started doing field work, about 1972, the cameras available with good enough lenses to take photos of plants or insects were big heavy single lens reflex cameras. My camera was so unwieldy that I only took it with me about once a week, and on that one day got whatever photos I wanted.

Photography wasn't easy. The macro lens unbalanced the camera, so it was hard to keep it stable. Worse, I had to get pretty close to the subject to focus, so the insects I wanted to photograph saw the big dark macro lens and moved to the other side of the stem or leaf.

Photographs were expensive. The slide film I used cost about $3 for 36 pictures, at a time that a Big Mac burger cost 60 cents. To get the film developed cost that much again. I tried not to waste any pictures.The change in availability of photographs is obvious to everyone. Cameras are found in cel phones; individual photos are virtually free. Beyond that, though, are technical improvements. Photographs are very fast today. In 1975, Stephen Dalton's book, Borne on the Wind, of insects in flight, was a revelation. Stop the action of a bee so that you can see the wings? Wow! Only since the 1970s. And now, video in everyone's pocket.

In 2000-2006 I studied winged wild buckwheat, Eriogonum alatum (buckwheat family, Polygonaceae), a plant of the Colorado Front Range. It has tiny flowers and no one had reported a pollinator. Pollinators were important because some plants have only male flowers (anthers with pollen, no ovaries), others only female flowers (no pollen), and a few have both kinds of flowers. What would visit the male flowers, which have no nectar? During that study, I twice put an insect net around a flower visitor, only to have it climb out through the mesh. It was that small. Looking at winged wild buckwheat again in 2018, I had video on my phone and got a murky video of something visiting the flowers:

This July I found a plant at Staunton State Park in the Rockies, and while I was there an insect flew up to stick its face into the (female) flowers and, presumably, drink nectar. I grabbed my camera and click! a good photo from which this wasp? can surely be identified (to family or genus if not to species). It wasn't very shy, but still, how far we have come! A good photo of a flower visitor without preparation.

|

| Insect visiting flowers of winged wild buckwheat Eriogonum alatum |

These improvements--from heavy expensive cameras using rolls of film to personal digital video--are just in my lifetime. Cameras go back only about 200 years. Before that, if you wanted an image you had to draw or paint it. Living things rarely stay still for that. Even the famous wave painting from Japan, The Great Wave (link) was done long enough ago, 1831, that he had to imagine how waves looked if stopped. Today we easily take a photo.

|

| In real life, the moment caught here was instantly gone. |

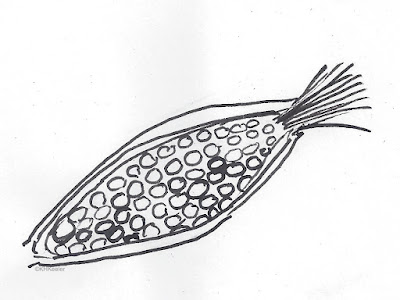

Our ability to grab images today was very much on my mind as I wrote my novel, I Have Seen Marvels, a Journey to Paraguay 1630. Much that was new to a European in South America was hard to describe well, since she would use Old World comparisons. Adding a picture made recognition much easier. So I illustrated the travel journal with sketches. I'm not an artist, but I have a biologist's habit of drawing something to remember what it looked like. The pictures let me write awkward descriptions for things unlike anything in Europe, corn ear as a "dry lentil-covered cane,"for example,

No comments:

Post a Comment