Not all the bright flowers are equally attractive to a bee. Flower shapes are functional. They encourage pollination, but pollinators come in various shapes and sizes, so flowers fit some pollinators and not others. Which, if you take the insect's point-of-view, means some flowers are food sources and others are not. Bees like flowers they can land on and then climb into the flower, or walk across tiny flowers.

To attract insects to carry pollen, flowers usually provide a reward, in the form of sugar water, nectar. Pollen containing sperm, needs to contact the stigma, where it will grow down the style to find the eggs in the ovary. Many insects visit flowers for the nectar but not all of them are effective pollinators. Some are too small, some get pollen on their bodies but wander away, not visiting another flower of the same species, some visit flowers in a way that gets pollen on their bodies but does not transfer it to the stigma. Plants have evolved specific flower shapes for effective pollen transfer and often, also, to exclude flower visitors that take nectar but don't pollinate.

|

| Missouri goldenrod, Solidago missouriensis with bees |

But this post is about how flowers look to bees. Here are some of the flowers in my yard, evaluated by a bee the size of a honeybee (Apis mellifera) or leaf cutter bee (Megachilid), or small carpenter bee (Ceratina), or andrena (Andrena), or sweat bee (Halictid), about 0.6", 15 mm, long.

Onion flower. The anthers and stigmas stick out. It walks across the surface, probing for nectar and bumping pollen onto itself and onto stigmas.

|

| onion, Allium cepa, |

With clustered bellflower (Campanula glomerata), the bee climbs in to take nectar in the center, where the arrow points. This flower still has a protruding stigma (white), but the anthers have fallen, they're the little c's in the flower center. This flower a pretty good size for getting pollen on the bee's butt, while it is probing for nectar.

|

clustered bellflower

|

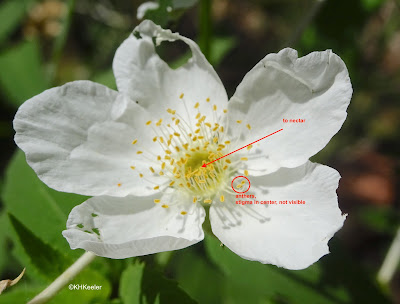

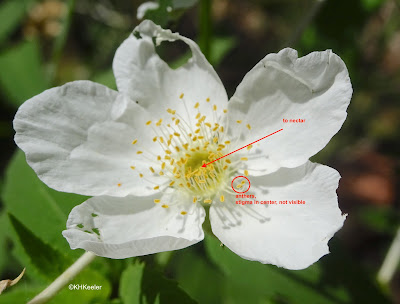

Apache plume,

Fallugia paradoxa, with a classical rose family flower. The nectar is in the center. Those are stigmas there, waiting for pollen to brush off all the anthers more scattered around the outside, as the bee probes the center for nectar. I don't have anything for scale: a honey bee is about as long as one of the petals.

|

| Apache plume, Fallugia paradoxa |

The double rose is in the same family and has a flower with the same basic plan as Apache plume, but the doubling of the petals obscures the route to the nectar. Often those extra petals make contact with pollen and stigma difficult, reducing or eliminating pollination.

|

double rose, Rosa

|

Western snowberry, wolfberry, Symphoricarpos occidentalis, is a good one for the bee. It sticks its head and thorax into the flower, probing for nectar that is down in the center. Easy access. The pollen brushes off on the back part of the head or the thorax, is easily transferred to the protruding stigmas on the same or other flowers.

|

| snowberry, Symphoricarpos |

Borage,

Borago officinalis. To get the nectar, the bee has to hang nearly upside down on the flower and probe between the purple protrusions. The pollen and stigmas are down inside, to be brushed against. Insects less able to hang upside down won't bother with borage flowers, so the bees don't have to share nectar with many others.

|

| borage, Borago officinalis |

Mexican hat, prairie cone flower,

Ratibida columnifera. The yellow shows the pollen, the stigma is hiding in there. A delicate movement of the tongue can draw nectar out of each of the tiny yellow-topped flowers, (A honey bee is a long as the cone is wide.)

|

| prairie coneflower, Ratibida columnifera |

Madder flowers, Rubia tinctoria. Smaller than the bee's face. Not worth trying to land on that flimsy stem and reach for a tiny drop of nectar. Leave these to really tiny bees and flies.

|

| madder flowers, Rubia tinctoria |

Daylily,

Hemerocallis fulva. Nice nectar way down inside, but the flower is so big the bee need not go anywhere near the pollen, let alone move it to the stigma. Most daylilies are a clone, so it doesn't matter much to their survival, but it represents a poor fit between flower and bees as pollinators.

|

| tawny daylily, Hemerocallis fulva |

Fireweed, Chamerion angustifolium. There is good nectar in the flower, but in a long tube. The sigma and stamens reach out where it is hard for the bee to bring pollen from the one to the other although those positions change as the flower ages. Nevertheless, it is not an easy source of nectar and the bee is not a good pollinator for it.

|

| Fireweed, Chamerion angustifolium |

This is dyer's greenweed, Genista tinctoria, from Europe, with a flower type common in the pea family. The flowers are closed and stay closed until an insect lands on the lower edge and pulls the petals open. Then the coiled up anthers and stigma spring out. A puff of pollen is shot at the bee. And a coiled stigma comes out to touch it, right where pollen from the previous flower should be. Only smart, relatively strong insects like bees learn to open these flowers. The nectar inside is worth the effort. First picture: unopened flowers. Second picture, you can see curled stigmas on opened flowers (red arrows). Pollinated flowers don't close up again.

|

| dyer's greenweed, Genista tinctoria, unopened flowers |

|

dyer's greenweed, opened flowers

stigmas sticking out (red arrow) |

Finally, bees, honeybees definitely, but also a number of other small bees, don't see red. The wavelengthst that make red are too short for their eye pigments, so look black. These striking Maltese crosses (Silence chalcedonica)

|

| Maltese cross, Silene chalcedonica |

probably looks like this to bees.

|

| Maltese cross as seen by bee eyes |

(not my best illustration, but you get the idea).

Of course, the flowers may actually be more visible to bees than my picture. Bees cannot see true red. If the flower has other shades, it could be attractive to bees, though it might not look anything like it does to humans. Butterflies and hummingbirds love true red; this flower is probably pollinated by butterflies in its native Europe.

So every plant is a story. Bees have to learn a lot to efficiently gather nectar.

Bees also collect pollen, which means they approach those flowers differently, as in this bigroot prickly pear (Opuntia macrorhiza) flower:

(if the video doesn't run for you, it shows the bee rolling around in yellow pollen.)

Watching bees visiting flowers is grand.

Comments and corrections welcome.

Kathy Keeler, A Wandering Botanist

No comments:

Post a Comment