|

| Study of harvest ant colony longevity; a few days of observation every year for 42 years |

Problems of long term data management fall into: "Don't count on memory" and "Don't trust technology."

Don't Count on Memory:

Write down ALL the details. Maybe you should imagine that the next person to collect the observations doesn't have you to ask. Expecting to remember all the details yourself is a happy illusion; after a decade, some bits get lost and you can spend frustrating hours trying to remember how you did it, when a 10-word note would have captured it. Suppose you give a GPS location for each plot. But what were the plot dimensions? 10 m x 10 m? 12 m x 12 m? And was your GPS in a corner (which corner?) or the center? It goes on like that, write down the details; that will make future work much much easier.

|

| I recognize this as my bush morning glory study, but what year? (squares are plants, lines represent gullies on the hillside) |

Were there special methods that you developed? Write them down. "When the plant had more than one flower stalk, we went N, E, S, W when recording them" or "When the plant had more than one flower stalk, we measured them from largest to smallest." (Important if you have earlier or later observations of that same plant.)

What are your notes like? Are ALL the abbreviations defined in several places? The meaning of "IG" describing a thistle just doesn't leap out. What the heck is "Max?" (Max was my Costa Rican field notes name for a small aggressive red ant, later identified as Solenopsis geminata; got a suggestion for IG?).

|

| Bush morning glory, Ipomoea leptophylla; they probably live 100 years; the permanent tag was often buried by the sandy soil. Record the location more than one way (tag, GPS, map, photo...) |

If you took notes on several pieces of paper, spend the time to write the date, place, etc. on EACH piece of paper; you don't want to be guessing based on paper type and ink whether it was 2017 or 2018. Likewise, if there are several files in the computer, make clear file names and repeat what the file is on the inside, every time; there won't even be differences in the paper and ink for clues if two data files get confused.

Assume the person writing up the study for publication isn't you...or that you will have forgotten a substantial portion of the details because of the three other projects you completed since this one was started. In short, spend the time each time that data is collected to label it properly and keep it organized. Otherwise, you get days of being angry at yourself.

And always, you need redundancy and backups. It is amazing which version is useable after 15 years and which is no longer helpful.

Don't Trust Technology:

It seems reasonable that our programs and equipment of today will be available in the future. And that's a bad assumption.

I started field work before computers. We were careful to use waterproof ink, but the handwriting was always tricky to read later. Then computers had small floppy discs, where data was typed (!!!), backed up and stored.

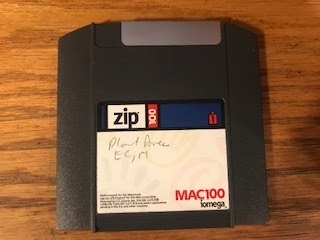

|

| Zip was a very big floppy disc |

Those got bigger but were replaced by compact discs. I thought compact disc technology nice and stable, so I put lots of stuff there, only to discover that from about 2015, computers don't have CD readers.

|

| CD; a good way to store data--if you can access it |

So those discs are in a box and I have to use a very old computer or an external disc-reader to access them. Originally I saw no flaws in storing data in thumb drives, but ports are evolving: USB 2, USB 3, USB...the older thumb drives are still supported, but may not always be. Backups to the cloud make sense, but I presume that among all the cloud storage sites, some will not always be there, for simple or weird reasons.

The farther into the future we get, the less compatible our current programs and equipment are with older ones. Usually you can find a way to work with old programs...but that method can be quite difficult, like crossing the city to the one library with a IT archive. Really a pain.

Not only the storage technology changes, everything computer does. Operating systems and programs are continually updated. Accumulating changes lead to incompatiblities. At some point the makers think nobody uses the old version and discontinues support. If you are changing with the times and ignore your stored files, you can find yourself unable to open data files you typed.

My recommendation is to annually open a few old files so you notice the changes. In the first year of the Next Best Thing, working with old files is pretty easy. It is three years later, when the necessary cord is somewhere in the bottom of the drawer, that it is problematic. You can prevent that by copying the files to the current technology. Strange to say, a reasonable alternative is to print the data so that there's a box with the raw data on paper, just in case. That won't be fun to retype, but, when you don't see how to access numbers in an obsolete format, that may be faster and less frustrating.

Backups are always a very good idea. Just make sure your labeling makes it clear which back up is most recent. And maybe, don't scatter them across several small storage places.

|

| "I'm sure I saved it to a thumb drive..." |

Did I say I've done most of this wrong? Oh yes. 1) The notes were on a field computer which I walked away from when the battery acted oddly; the unorganized backups were scattered across at least six thumb drives. So frustrating. 2) The annual observations were printed and put into a paper folder, but I had to deduce the year by finding where it fit in the progressive decrease in number of ant colonies recorded. Not a comfortable method for that one last page with only 3 entries. 3) "MND" meant mined, as in drilled by leaf-miners; or did it mean mound, that the plant was growing on a pocket gopher mound? Sometimes context was clear, sometimes I just guessed. 4) And I have carried all my floppies the archive of the campus IT office to access a program I once used daily.

If you complete studies in the usual 2-4 years, these issues don't come up. The study is summarized, described, and published with current technology. It is when you want to use ten-year-old data that you get to reflect on the rate of change, despite the fact we think we'll stay with the current methods or ones very like them, indefinitely.

Don't worry, even when, with preparation you avoid the hassles above, there will be some other change to infuriate you. Remember we call it progress!

Comments and corrections welcome.

No comments:

Post a Comment