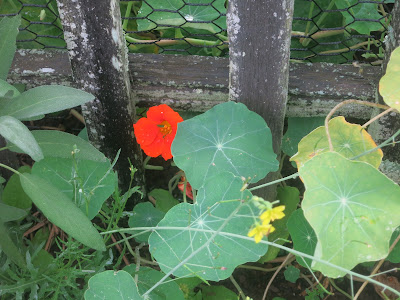

Nasturtiums are easily-recognized garden flowers. They have big orange (or red or yellow) flowers with a long spur and interesting round leaves with the stalk (petiole) in the center. They are also edible.

|

| nasturtium, Tropaeolum |

The scientific name for nasturtiums is Tropaeolum, and they are in a distinct plant family, the Tropaeolaceae. All species in the Tropaeolaceae are found only in western South America. All the 90-105 species of plants in this family are so similar that they are classified in a single genus, Tropaeolum. At least five species of Tropaeolum can be purchased for gardens. The most common garden plants are T. majus and T. minus.

Disconcerting to people trying to look up nasturtiums, in garden books for example, is that nasturtium is the genus name for watercress, Nasturtium officinale. When Tropaeolum was brought to Europe, people likened the taste to watercress, which they called nasturtium. The name nasturtium stuck with these exotic flowers as a common name and Nasturtium officinale came to be called watercress. (see previous post on the confusion: link). That is, the American species stole the European plant's common name.

|

| nasturtium Tropaeolum |

Nasturtium was the name Romans used for cresses, such as watercress (Nasturtium officinale) and wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris). There are numerous, hard-to-distinguish cress species that Europeans didn't work hard to tell apart. My friends who forage for wild cresses, we'd say wild mustards or wild brassicas today, likewise know they are all edible with a similar sharp taste and don't worry very much about which mustard it is.

The species epithets of Tropaeolum, majus and minus, mean, respectively larger and lesser. The genus name, Tropaeolum, is based on tropaion, Greek for trophy, or more precisely, monument to an enemy's defeat. The Greeks sometimes hung the helmets and shields of the defeated on a pillar at the site of the battle. A plant of nasturtium growing on a post near Linnaeus's home reminded him of these Grecian monuments, the round leaves of the plant like the round shields of the Greeks, and the spurred flowers, with patches of red, like helmets, so he chose Tropaeolum for the scientific name. We don't usually think of classic botanists having flights of fancy, but, clearly, this was one.

Nasturtiums, whether you munch the flower or the leaves, have a spicy taste that does remind you of watercress. They are excellent as additions to a salad, as a pesto, as an edible garnish on mashed potatoes and much more (links to recipes, more recipes). They've been eaten for millennia. They were cultivated for food in South America 8,000 years ago. Europeans started eating them right after their arrival, for example there are recipes for pickled nasturtium buds from the 1750s.

In the garden, nasturtiums grow quickly from their big seeds and produce a cascade of big flowers. Some species available from seed stores are quite viney, others creep across the ground. They are grown for the flowers--I love the big bright blossoms--or cut for bouquets and flower arrangements, grown as a vegetables or planted as companion plants to lure insects away from lettuce, cabbage, or squashes (they grow fast enough that the insects don't eat them up and then return to other vegetables.) They grow better on poor soil than good soil, so are a go-to plant to fill in problem areas.

Europeans originally called them Indian cress, Indian referring to the New World. Eventually the common name became nasturtium. European plant lore says they sprang into existence from the blood of a Trojan warrior; the flower with its spur was his helmet, and the round flowers his shield. Nice story, but nasturtiums were unknown to the Trojans. This story must have evolved from Linneaus' ideas in naming them. In the Victorian language of flowers nasturtiums represent patriotism and are still used that way today, if, for example, you are choosing wedding flowers for their meanings.

|

| nasturtium Tropaeolum |

Comments and corrections welcome.

References

Allardice, P. A-Z of Companion Planting. Angus and Robertson Books. Pymble, Australia.

Bremness, L. 1994. Eyewitness Handbooks: Herbs. DK Publishing, New York.

Donna. 2015. Flower Tales--Nasturtiums. Garden's Eye View blog. link Accessed 12/17/22.

Greenaway, K. 1979. Originally 1884. Kate Greenaway's Language of Flowers. Avenel Press, New York. Online. link Accessed 12/17/22.

Hollis, S. 1990. The Country Diary Herbal. Henry Holt and Company. New York.

Judd, W.S. and G. A. Judd. 2017. Flora of Middle-Earth. Oxford University Press. London.

Smith, A. W. 1997. A Gardener's Handbook of Plant Names. (originally published 1963. Dover Publications, Inc. New York.

Kathy Keeler, A Wandering Botanist

More at awanderingbotanist.com

Join me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AWanderingBotanist

Wow, that's really interesting! Thanks also for the links to recipes. My mother in law's garden has a good crop of Nasturtiums, and it's good to have some more ideas for how to use them!

ReplyDelete