The conservation community is urging people to grow plants native to their area. At the same time, you can find articles arguing against planting cultivars of native species. It is difficult, buying a native plant, to figure out how to avoid a cultivar. And why should you? This is a big topic. I'll cover it in a series of posts. First, why grow natives at all?

|

| Natives beebalm, black-eyed susans and a bit of grass |

Growing natives is a move to get everyone to participate in conserving the native plants and animals of their particular region of North America (or wherever you live). Europeans came to North America and brought the plants and animals they depended on, from wheat and apples to cows and chickens. They tucked in a few herbs and ornamentals, such as lavender and roses. Many weeds came along, either because they were used as food or medicine (dandelions) or stowed away (cheatgrass). The natives were plowed up to make way. Agricultural land and urban yards filled with plants and animals from Europe.

You could, and still can, walk down a suburban street and see virtually no native species. Or stroll downtown and see lots of planted trees, shrubs and bright flowers, all from elsewhere. Or drive through the countryside and see fields of crop plants from Eurasia and beside them, European weeds filling the ditches.

|

| Introduced plants, all except the Colorado blue spruce behind the garage |

The problem is that plants and animals have complex co-evolved relationships. The larvae of butterflies and moths of North America have only a few plants they can eat. At one time those plants were common. But they've been replaced by nonnatives. We didn't notice.

To protect themselves from being eaten, plants evolve defensive chemicals or other protections that keep most insects from eating them. Over millennia, insects respond by evolving mechanisms for avoiding the poisons or spines. Those adaptations cause the insects to specialize on particular plant species. Thus, in its native range, plants have insects that eat them. When you move a plant to another continent, you leave behind its specialists and it now grows in an area where none of the local insects can eat it. That is what we have done, turned North America into miles and miles of Eurasian plants, that our native insects cannot eat.

|

| Moth larva eating evening primrose (Oenothera), western Nebraska |

Then somebody observed that there aren't as many insects as in the past. Insects are very diverse and numerous, so they are hard to count. But as of 2017, beetles, dragonflies, grasshoppers, and butterflies were documented to have declined in numbers by 45% over 40 years.

Birds, for example chickadees, robins and warblers, require literally thousands of insects to feed their chicks until they are ready to leave the nest. Without half the insects, we can expect only half the birds. Bird numbers are on the average down by 25% in the last 50 years with some species already reduced by half.

Birds need more insects, insects need more plants they can eat. What should we do?

In the U.S., about 12% of the land is protected and could be expected to support native plants growing native insects, growing birds. Which sound like a lot, except if those are the only places where natives reproduce, insect and bird numbers will be down 88% from presettlement times. That means most people most days will see barely one butterfly or bird if they are not out all day looking.

We are not going to expand protected areas to even 50% of North America. So Doug Tallamy and others propose that everyone pitch in and grow some plants that are native where they live. This will greatly increase the food available for American insects and so for birds. (This has been called Homegrown National Park see link). Planting natives will help other kinds of North American animals because they either eat plants or eat another animal that eats plants, so making more potential food will help them as well.

|

| skipper butterfly on purple coneflower (Echinacea) |

Another reason to grow plants native to your area is because that is their home. They grow there best. We should proudly grow the plants of our region, and show them off. And make our yards and parks distinctly Colorado or clearly Tennessee or impressively Oregon, not all the same.

The movement to plant milkweeds (Asclepias species) to help monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) is a good example of "grow natives." Monarch caterpillars eat only milkweeds, a group of plants native to North America. Milkweeds have been treated as undesirable plants and eradicated when fields are planted, roadsides cleared, or neglected lots cleaned up. Monarchs numbers dropped 85% in 20 years (99% on the West Coast). Numbers increased briefly in 2021 but are down again. But planting milkweeds so that more monarch caterpillars grow to be butterflies remains the best solution anyone has yet thought of. It is a continent-sized problem.

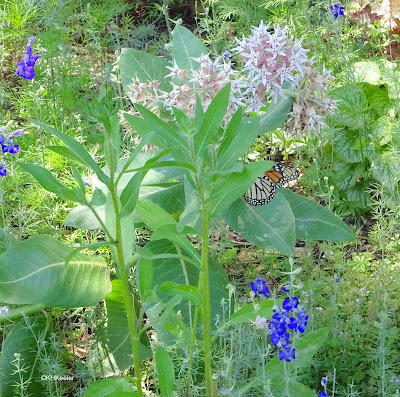

|

| monarch on milkweed |

The above picture is a success story, sort of. I live on the western end of the range of eastern U.S. monarch butterflies, up against the Rocky Mountains. (Monarchs don't go high on the mountains). So I planted our local milkweed, the showy milkweed, Asclepias speciosa, and this summer, the plant's second year, wow! there was a monarch. "If you plant it, they will come." However, I never saw any eggs or caterpillars. It is necessary to have milkweed plants for monarch reproduction, but it is not enough. The butterflies must lay eggs and the caterpillars must survive. Well, the plant will doubtless grow bigger. Maybe when I have an inviting clump of milkweeds, not just three stalks, I'll discover caterpillars.

The monarch-milkweed story repeats over and over for the native butterflies and moths of North America (about 14,300 moths and butterflies that feed on some 17,000 native plants, so probably 17,000 versions of the story). Preserves are not enough, all of us must be part of the solution, and planting native plants is key to feed our native animals.

|

| A patch of natives: coreopsis (Coreopsis), sulfur flower (Eriogonum) and Louisiana sagewort (Artemisia ludoviciana) |

Next post: what to plant and about cultivars of natives

Comments and corrections welcome.

References

Center for Biodiversity. Saving the monarch butterfly. Center for Biodiversity. link (Accessed 10/21/23)

Cornell Lab. 2019. Nearly 3 billion birds gone. Cornell Lab. link (Accessed 10/21/23)

Oberhauser, K. 2023. Monarch winter 2022-2023 population numbers. Journey North journeynorth.org link (Accessed 10/21/23)

Rosenbaum, M. 2022. More than half of U.S. birds are in decline, warns new report. Audubon Oct. 12, 2022. link (Accessed 10/21/23)

Wagner, D. L., E. M. Grames, M.L. Foreister and D. Stopak. 2021. Insect decline in the Anthropocene: death by a thousand cuts. P.N.A.S. (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA)) 118 (2) e2023989118 link (Accessed 10/21/23)

No comments:

Post a Comment